Book vs. Comic vs. Film: How Do Superheroes Translate Across Media?

“Novelizations of films are generally not thought of in artistic terms whatsoever…. If you’re lucky, you get some extra background, a window into the character’s heads. If you’re not lucky, you end up with a movie script punctuated by blocky narrative.” – Emily Asher-Perrin on the Revenge of the Sith novelization

Recently, Marvel released a traditional novel about Miles Morales, a.k.a. Spider-Man. While writing a pictureless book about a comic book character might seem odd, cross-media storytelling isn’t new. Many comic book films have novelizations of their own.

Translating a traditional book to the screen is difficult. What happens when a comic book’s story is retold on film and in a traditional book? What details are lost? In this group presentation, your students will study how certain stories are retold in comics, books, and film.

{Image is a top and bottom comparison of the Civil War comic and the Civil War film. The top half of the image is from the comic, featuring most of the characters involved in the fight. The bottom half of the image is from the film, featuring most of the characters involved in the fight. In both images, the characters are in profile, facing off.}

Students will engage in cooperative learning, visuals, a project, and a presentation.

Materials Needed:

- Books based on comics or on films (the Marvel Civil War novelization; any of the recent novelizations of Marvel films; the Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith novel)

- Comics (Marvel Civil War; Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith; The Dark Knight)

- Films (any of the recent Marvel films; Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith; Batman)

- Computers with DVD drives so students can watch the films

- Headphones so students can watch the films

- Trifold posters (try the Dollar Tree)

- Markers

- Printers

- Glue sticks

Standards Met:

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.9-10.7 Analyze the representation of a subject or a key scene in two different artistic mediums, including what is emphasized or absent in each treatment (e.g., Auden’s “Musée des Beaux Arts” and Breughel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus).

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.9-10.4 Present information, findings, and supporting evidence clearly, concisely, and logically such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization, development, substance, and style are appropriate to purpose, audience, and task.

- Ask the students to name some books that have been turned into films. Have them describe the differences between the book and the film adaption. Have them wonder what caused those differences. This should only take a few minutes.

- Explain to the students that over the course of the next several class days, they divide into groups and study the differences between comic books and their film and book adaptations. They may also study the differences between films and their comic books/novelizations. At the end of the unit, the groups will present their analyses to the class with the help of a trifold poster visual aid.

- Divide the students into groups of three. Have these groups pick one story from a series of options. Some good examples of book/film/comic trios include Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith, Marvel Civil War, and The Dark Knight. Have the groups decide which student in the group will read the book, which student in the group will read the comic, and which student in the group will watch the film. “I Can” Statement: I can work productively with a group to plan a project.

- Give the groups time in and out of class to read and watch their books/comics/films. If possible, it may be helpful to your students if you provide movie nights when they can come to school and watch the assigned films. Remind students to watch and read carefully and to take notes. “I Can” Statements: I can read a text carefully and analytically. I can watch a film carefully and analytically.

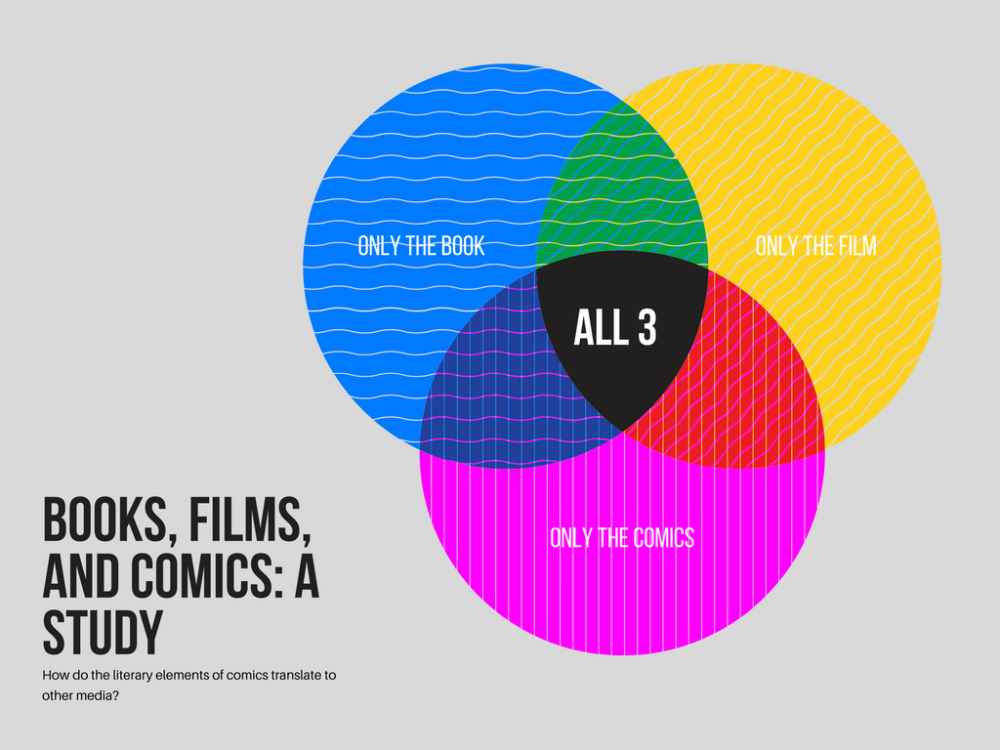

- In class, have the students create a Venn Diagram of what they noticed in the book, the film, and the comics? What similarities were there? What differences? Using this information, the students should come up with a paragraph outlining their plan for their presentation. “I Can” Statement: I can synthesize information using a Venn diagram.

{Image is of a multicolored, computer-generated Venn diagram. The entire diagram is entitled: “Books, Films, and Comics: A Study” and subtitled “How do the literary elements of comics translate to other media?” One circle in the diagram is labeled “only the book,” one is labeled “only the film,” one is labeled “only the comic,” and the center is labeled “all three.” The other overlapping parts would correspond to similarities between book and comics, book and film, and film and comics.}

- Have each group show you their Venn Diagram and presentation proposal. Discuss their ideas and suggest any necessary improvements. “I Can” Statement: I can use a teacher’s suggestions to revise or redirect my work.

- Once you have met with the groups, provide them with a trifold poster and craft supplies. Remind them that this poster should be a good visual aide for their presentation. The poster is a trifold poster because they are discussing three forms of media. If the groups are struggling, describe the process as translating their Venn diagram onto the poster. “I Can” Statement: I can create a neat, informative poster.

- Have each group give a 5-to-10-minute presentation about their findings. Their presentation should cover the literary elements of each form of media as well as their personal conclusions: did the story translate well from its original medium to the others? Why or why not? Each person in the group should have equal responsibility for communicating information. “I Can” Statement: I can work collaboratively to present coherent literary analysis to an audience.

What differences did your students notice in their literary analysis? If you and your class are doing something super, please let me know in the comments!