What Do You Mean They’re Making Heroes Register? Censorship and Comics

“This nation was founded on one principle above all else: the requirement that we stand up for what we believe, no matter the odds or the consequences.” -Steve Rogers/Captain America, Amazing Spider-Man #537

The comics industry is no stranger to censorship. The Golden Age of comics, from the late 1930s through the early 1950s, morphed into the cookie-cutter Silver Age due to government interference. The 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent claimed that comic books were an evil force that seduced children into delinquency.

While in retrospect the concept of comics as a malevolent entity might sound as out-of-style as McCarthyism, the reality is that many adults still fear the persuasive power of reading. How else can we explain the need for Banned Books Week? While current comics, especially those outside the Big Two (Marvel and DC), are permitted tackle darker narratives, they face opposition in school libraries across the country. Groups such as the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund fight to protect comic books’ place in schools.

In what ways does censorship affect how students interact with comics? Today’s four-day lesson plan introduces students to the concept of censorship through the lens of banned comic books.

{Image is of a CBLDF poster for Banned Books Week 2014. A group of comics characters, including Captain Underpants, cringe away from a group of protesters carrying signs that read “Ban This Filth!” A person clutching a book has their arms spread in front of the comic book characters. He says, “Defend banned books!” Image comes from http://cbldf.org/2014/09/free-posters-and-resources-for-banned-books-week/}

Students will engage in discussion, whole group instruction, independent activities, and a project.

Materials Needed:

- Banned comic books/graphic novels such as Drama, Persepolis, Maus, This One Summer, and Bone, enough for one per student (with any luck, you can find them in your school’s library or your public library!)

- Lined paper or notebooks for outlines/note-taking

- Computers and printers available for students to type essays

Standards Met:

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.9-10.1 Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.1 Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.

- Begin class by mentioning that this week is Banned Books Week. Ask the students if they have heard of this and what it might mean. This should only take a few minutes.

- Ask the students to tell you what they know about why and how books are banned. This discussion should take five to ten minutes.

- Have the students read this Washington Post article about the recent increase in illustrated banned books and discuss it with a partner. After ten minutes, have the students present their ideas to the class. Be sure to encourage active listening—instead of asking the students what conclusions they drew from the article, ask them what their partners thought of the article.

- Explain that over the course of the next few class periods, the students will each choose a banned comic book to read independently. In a well-crafted MLA-style essay, they will analyze the book’s structure and the author’s intent. Then they will have to research and address why the book was banned and argue for or against its banning.

- Allow the students the remainder of the period to choose and begin reading their banned comic book.

- By the next class period, students should be mostly finished with their comic books. In class, have them research why the book was banned and what the outcome of that banning was. Was the book permanently barred from certain schools or libraries? Did the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund or another group come to the comic’s aid? Allow the students to work on their essay outlines independently.

- Outside of class between the second and third class periods of the unit, students should craft a first draft of their essays. Assign them a partner to peer edit their work. Some good peer editing questions:

- What was the intent of your essay?

- What do you think your thesis statement is?

- Could you clarify (a confusing section)?

- What do you think the book you read was trying to get across to its readers?

- Why was this book banned?

- Outside of class between the third and fourth (final) class period of the unit, have the students use their peer editing remarks and their own editing to craft a polished final draft of their essay. Some rubric ideas:

- Did the student summarize the plot of the comic book they read?

- Did the student address the reasons why the book was banned?

- Did the student address their own thoughts on the book?

- What conclusions did the student draw? Did they back up their ideas with evidence from the text and art?

- Is the student’s spelling and grammar correct and consistent?

- Did the student cite the book itself and any research using correct MLA-style citations?

- After the students turn in their essays, have them form groups and discuss their findings. Remind them to be active listeners: when the groups come together as a class, they will have to explain another group member’s essay to the class. Help the students to discern what they think about the stories they read and what they feel about censorship. If they have any questions or concerns about what they read, they may respectfully discuss them at this point.

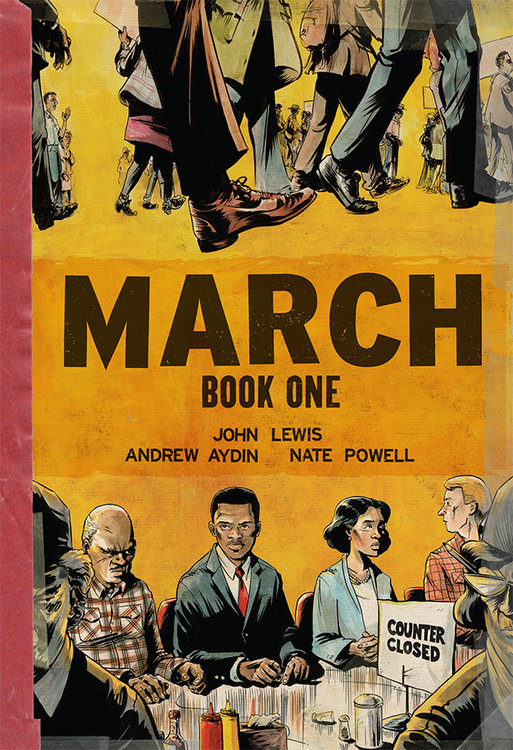

Some suggested books:

{Image is the cover of Drama by Raina Telgemeier. There are three illustrated characters walking across a stage in profile: two boys with a girl in the middle. The girl has a heart over her head.}

Drama is the story of a middle-school girl who participates in, you guessed it, theatre. She ends up falling for another theatre kid, but things get complicated, as junior high crushes often do. This comic has been banned due to LGBT themes.

{Image is the cover of Art Spiegelman’s Maus. Two anthropomorphic mice stand with their arms around each other. Behind them is a swastika with a cat’s head superimposed on it.}

Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel Maus has been banned because it addresses the violence of the Holocaust head-on.

{Image is the cover of Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi. A girl wearing a hijab is at the very center of the otherwise bare red background.}

Persepolis, a graphic memoir by Marjane Satrapi, has been banned because it discusses Islam.

If you or your students are interested in reading more resources about banned comic books, check out these links:

The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund’s Banned Books Week page

The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund’s Banned Books Handbook

Using Graphic Novels in Education

What are your students’ thoughts about banned comic books? Which banned comic books did they enjoy the most? If you and your class are doing something super, please let me know in the comments!